MY paternal grandfather’s abiding passions were his vegetable garden, barley wine, horse racing and Newcastle United Football Club – not necessarily in that order.

But one thing was certain, enter his living room any time after 4.40 on a Saturday afternoon – once the BBC tele-printer was running – and there was complete silence, as he waited for the Newcastle result to come in.

Grandfather, or Pop as he was known, was born and raised in Throckley, seven miles west of Newcastle upon Tyne, the son and grandson of coal miners at the village’s Maria Pit. He was Geordie to the bones.

He had moved south in 1933, during the Depression, with my gran, my dad and his three siblings, to find work and a better life.

With his health failing, aged 86, he returned north early in 1979, following the death of my gran. He wanted to live out his final years on his beloved Tyneside.

All my life he had regaled me with deep passion about the pre-war Newcastle teams (particularly the 1926-27 First Division champions) and the three times post war FA Cup winners, with the legendary centre forward Jackie Milburn – the uncle of Bobby and Jack Charlton.

So we come to the evening of Friday 4 May, 1979, and I am sipping a large whisky with Pop at his comfortable new home on Tyneside and talking excitedly about the reason I am staying with him for the weekend.

I am enthusing about my beloved Brighton and Hove Albion and their end of season fixture at St James Park against his beloved Magpies.

He smiles, asks me to pour him another whisky – this time with a splash of ginger wine – and whispers: “Don’t get carried away lad, your team haven’t done it yet, they still have to encounter the Mags on God’s own soil.”

I went to bed that night with a huge grin on my face.

Saturday 5th May was our big day.

But strangely, it wasn’t the last day of the 1978/79 season.

A snow laden winter had left many clubs playing catch-up with their remaining fixtures, and we were going into our last game at Newcastle, at the top of a remarkably tight Second Division table, with just one point separating the top four clubs.

A win would secure us promotion to the First Division for the first time in our history against a Newcastle side in ninth place, with little to play for, bar pride.

So that morning, in bright sunshine, but with a chill wind in the air, I hopped the local train into the city.

At the station I met an old friend Pete – a Geordie with whom I had gone to many Newcastle games, while we were at university together in West Yorkshire. He had a black and white scarf wrapped around his neck and was grinning widely.

“Why aye, Nic, let’s do some beer,” he enthused, “There are quite a few pubs that open at 10.30.” And so we began a two man pub crawl for the short distance between the city station and the Newcastle ground.

We eventually reached The Strawberry, an infamous drinking hole outside the Gallowgate End of St James Park. It was (and still is) a pub for home supporters only.

“Keep yer trap shut inside,” Pete winked, “Or I am not responsible for taking you to hospital!”

The Gallowgate End or “Gallows Hole” was an historic place of public execution in Newcastle. In 1650, 22 people – including 15 witches – were hanged in one day.

The last hanging took place in 1844, only three decades before the first ball was kicked inside St James Park!

So I drank my pint quietly, to avoid becoming a 20th century execution!

Then, merry with beer, Pete and I shook hands and wended out respective ways to either end of this legendary football stadium. What followed, was the stuff of real legends.

The weather was sunny and dry as the game kicked off, in front of 28,434 fans.

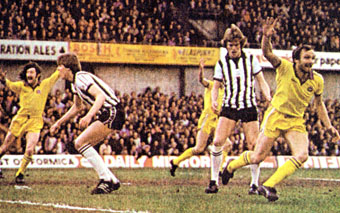

The first 10 minutes was all Brighton as we attacked the Leazes End, where our 2,000 plus fans were gathered. We were dominating, and suddenly from a left wing Williams’ corner, skipper Brian Horton snuck between the Newcastle defence to bullet a header into the net. (1-0 Albion).

With Rollings and Cattlin immense in defence, Horton running the midfield, and Peter Ward inspiring, Albion began bossing the game. A few minutes later Ward let Maybank in with a clear shot on goal, but Teddy shanked it wide.

That was the key for Newcastle to up their game, and they twice came close to an equaliser.

But they hadn’t counted on Peter Ward, whose sublime mazy run through their defence and a directed shot, which somehow managed to cross the goal line, doubled the lead. (2-0 Albion).

Our football was expansive as the rain started to team down.

It was end to end stuff, before Ward fired at goal and Gerry Ryan poked in the rebound from a Newcastle defender. (3-0 Albion).

But the Magpies were not about to give up and they began to put steady pressure on our goal before the half-time whistle blew.

We were almost there… just 45 minutes to make history.

The second half was rocky in comparison as Brighton nerves made their way around St James Park. But the clock was ticking and when Alan Shoulder pulled one back for Newcastle, it was too late for a comeback.

As the final whistle blew, the moment (and the game) was savoured. We went wild as our heroes in yellow ran towards us, manager Alan Mullery ran onto the pitch, hugged Horton and joined in the celebrations.

Tears flowed, voices shouted, cheers echoed, hugs were exchanged and smiles enveloped every face.

We were promoted to the top flight for the first time in our history!

But it had gone to the wire: with a game in hand, Palace won the title with 57 points, we were second on 56, just ahead of Stoke on goal difference and Sunderland fourth on 55 points.

After the game I tried to find Pete for a celebratory pint, but in the days before mobile phones, and amid thousands of cheering supporters, the task was impossible.

A few days later, he telephoned me at home to say; “Where were you afterwards? We were all waiting for you in The Strawberry!”

But later that sublime Saturday evening I arrived back at Pop’s home, to be greeted with a smile, a handshake, a “well done, lad” and a very large whisky.

Pop sadly passed away, two years later.

I will never forget him, or that day.